BLOG #141 3/8/16

Thumbing through a new book.

At home, in your hands, you have a new book, a book of photographs, a monograph filled with images made by one artist.

Maybe you received the book as a gift. Or you bought it in a favorite bookstore, or – dread the thought – online. You hold onto it, still wrapped in plastic. Now what?

Do you place it on a table or your desk, remove the plastic, open it, and using your left thumb (why this occurs so frequently, I’ll never know), start from the back and flip rapidly through the pages?

Or do you retire to a favorite easy chair and take the time to actively study its contents? Do you open it in back, the usual location for “About the Photographer” information? Or, open from the front to read the introduction, usually written by someone other than the photographer? Or do you skip the intro (perhaps not wanting to be told what to think) and go right to the first image?

And then what? How do you look at the images? Do you spend a fraction of a second with each, turning the pages from front to back, only stopping when there is an especially appealing image?

Or do you spend just a second or so with each image as if scouting a location site for an event – just to get a “feel” for what the artist and his or her images are about?

Perhaps you spend considerable time with each new book, and think about meaning and subtext; what is the photographer trying to say, what is the music he or she hears, what is he/she feeling, why was that item included, what was a particular cropping meant to convey? Or is the photographer just exclaiming: “Hey, look at this! Pretty cool, huh?“

I have learned almost as much by studying such books, the work of others, as I have from making my own images. I love looking at photography books. I have discovered, for my own capacity to retain visual imagery, that I must look, ponder, then look again and again. I’ve found that I gain more understanding with each visit to a book or a single picture.

And so, after completing my first look, I now know that the very worst thing I can do is to close the book and put it on a shelf. The shelf is a killer. Shelving a book after one look almost guarantees it will never be opened again. Intended as a future reference source, the book instead becomes mere decoration. Having not been really studied, it sits neglected with other similarly once-seen monographs. Might as well give it away.

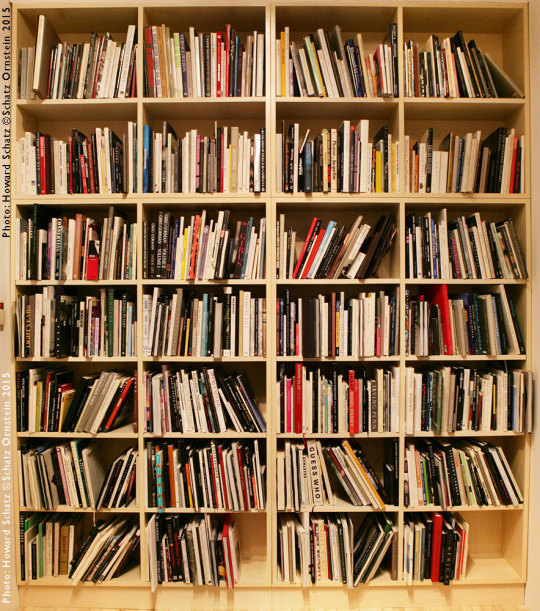

These shelves hold about 50% of my books of photographs. A bookshelf can be a graveyard for books, or a readily available reference source.

In order to avoid this sad fate, the death of a book, after my first look at the images of a new monograph, I leave it out, open to any page, on a desk, table, or counter top that I pass by frequently in the course of a day. And I will stop and take another look, sometimes just turning one page, becoming familiar with an image I had looked at before. I might spend a minute or five, with just a few images. The book remains out until I’m satisfied with my understanding of the work. It might be out for a few weeks or even months, but I don’t put it into the book case until the work, or just an image or two, are in my memory as a reference source for future; my visual data bank.

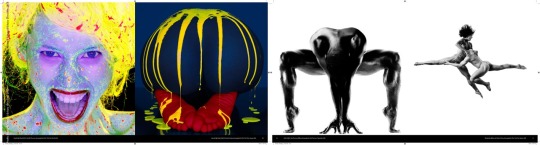

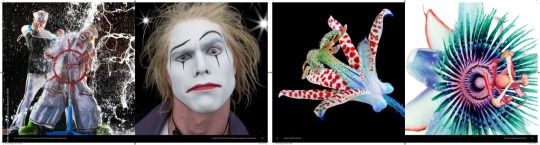

The great San Francisco architect Jim Jennings has a copy of my two-book retrospective (http://schatzimages25years-glitterati.com) in his South of Market office. The two books are opened, side by side, on a centrally located work desk. The combinations of the four images, two from each book, lined up make for an infinite visual display. He, or one of his talented assistants, only has to turn one page in each book and another unique four-part collage of images is created. Here, a few examples of page turns from Books One and Two.

Flip a few pages, and, voila!

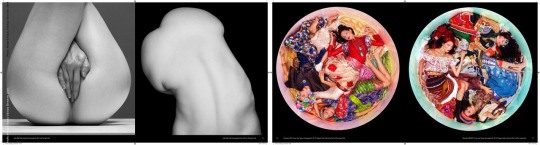

Little later, turn again….

And, once more, perhaps at the end of the week….

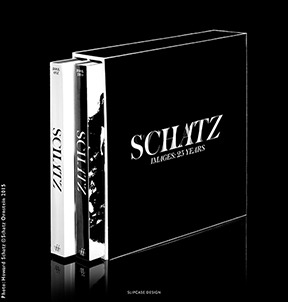

How else can one appreciate and understand over 1000 images from 25 years of work? To sit for hours with the two large books, studying each image, just isn’t consistent with a busy life. I sometimes think that the mistake we made in the design was to create a box into which the two books fit perfectly. This kind of neat package just begs to be put to bed neatly on a book shelf – a death sentence! Our desire to have the two books so elegantly contained may be a prime example of the old adage, “The perfect is the enemy of the good.”

Perhaps we had a “two book problem.” Many other photographers who have had long, successful careers – I think of Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, particularly – published their work in a series of books, not all at once. I’ve done this too, with 20 publications that collect everything from my underwater work to studies of prizefighters. But Beverly and I wanted to put the “body” of what we’d done under one cover. Or rather, two. Hence, the box.

The two-books in their box.

Other large monographs potentially suffer the same fate. The massive Helmut Newton retrospective, SUMO, a titanic book, measures (20 x 27.5 inches) and weighs approx. 66 lb. To avoid one’s burying the book on a shelf, the publisher (Taschen) provided a beautiful book stand designed by Phillippe Starck; a great solution.

Other monographs have been boxed as well, and suffer the same fate of the shelf as cemetery. The massive Peter Beard retrospective from a decade or so ago (weight: 36 lbs.) was contained in a large box, shelf worthy even though not many shelves could hold it. The publishers, knowing how the box led to neglect, included a wooden platform that let the book be left out for daily page turning in the way architect Jennings invites inspection of my two books.

So, to those of you who have spent significantly on my retrospective and the attractively packaged monographs of other photographers, here’s a suggestion: remove the books, open them up, leave them out, peruse them from time to time; savor their splendor, revel in their glory, make them immortal.

And, place the elegant box, back on the shelf, empty.

Link to the Two-Book Retrospective: http://schatzimages25years-glitterati.com