I’ve made portraits ever since my first serious venture with photography:

Gifted Women. Over the ensuing months I plan examine Photographic Portraiture in a series of posts using portraits I’ve made and continue to

make—I prefer the term “create,” as imagination, invention and discovery are necessary. Collaboration, as well.

At 83 years of age, Sigmund Freud was stricken with terminal cancer, but he “died in his chair,” still seeing patients. He wouldn’t stop because nothing fascinated him more than human beings. I am similarly intoxicated by people; my fascination is with human physiognomy and what it tells us about a person’s inner life. Portraiture is so compelling to me that when I see an interesting face on the street I can’t help staring. New York City streets are a treasure trove of faces, and though I haven’t got into any trouble so far, I have come close.

I have read a great deal about portraiture in the work of art historians, critics, painters and photographers themselves. Most have had theories, opinions and convictions that have been of interest and often of value to me. During years of studying and working with my camera, I have formed some of my own thoughts and ideas as well. Given the wide range of human complexities, I still have much to learn.

Why is the portrait being done – what is its purpose? If the portrait is being made for the request of the subject (the sitter), then vanity informs all efforts. When it is for a third party (not the sitter and not me) such as a magazine editorial or advertisement, the photographer has to find out what the editor or art director has in mind: what do they want the image to say. In such cases I remove my own desires and ego from the endeavor and carefully tune in to the wishes of another. I become a fine craftsman.

When I am making the portrait for my own artistic purposes, I do not think about anyone else. I strive to create an image that gives me a jolt—it might be one of revelation or surprise or joy. The classic question: What makes a great portrait, one that has the emotional power to stop one in his or her tracks, to look, examine, interpret——wonder? And many other factors: these questions will be examined and discussed.

The elements that make up any portrait are many including lighting, props, place, perspective, design, composition, contrast, pose, gesture, the sitter’s attitude, and sometimes even a trick or gimmick; and of course fame, or recognition. Finally, and inexplicably, when things really work, there’s a kind of magic that results in an image that moves and amazes.

My desire, when creating a portrait (what I want for myself, not the sitter, editor, or anyone else) is to produce something unique and that I love. This is a very, very difficult thing to do. I’m at a place in my creative life where I can make a “good” photograph at virtually any sitting. But making something spectacular takes all the ingredients mentioned above and then even more. One essential, in my opinion, is to earn – quickly – the trust of the sitter, and then after having done a great deal of preparation and creative thinking, take as much time as possible, and then hope for the kind of elusive magic that perfuses the studio and washes over the sitter, as well as me. Such moments are gifts, the generosity of the gods, a famously whimsical group.

These are eight of the portraits that I feel “worked,“ and why I think they did.

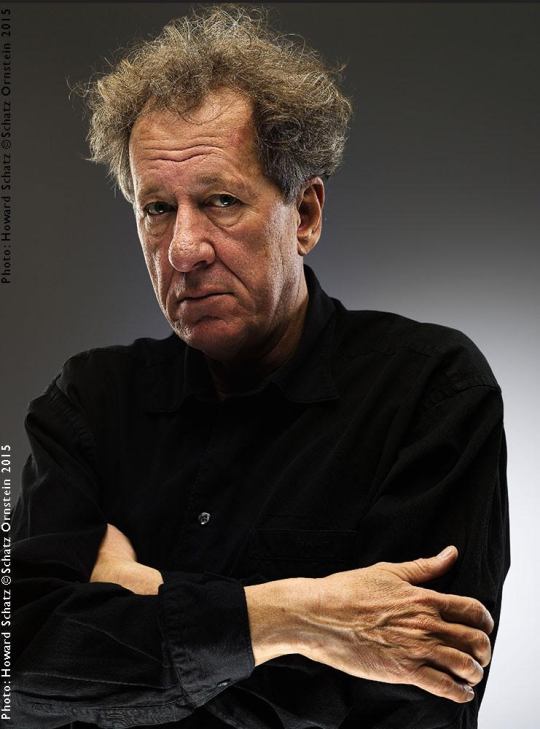

Geoffrey Rush

I worked with this instantly recognizable actor to achieve veracity. Actors sometimes have a hard time not “doing something” for the camera to affect the result, which is how they make a living. Even when they try to do nothing, one can see them working, however subtly. Often my approach is to take a few minutes explaining what I want to do. Then, when I see that they understand what I am after, I talk and observe, waiting for the actor to just listen as they look at me, paying attention. Then I will say, “There! as you’ve been listening to me, “perform” has disappeared. Can we try that?” This works, sometimes, and sometimes not. When not, I proceed to other methods. It may take a long time, a commodity that is rarely available when you have a celebrity in front of your camera.

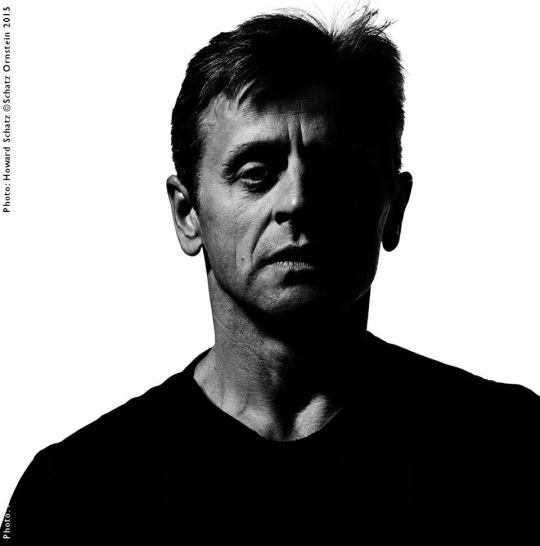

Mikhail Baryshnikov

Preparing for this sitting, I did extensive research and found hundreds of images of Baryshnikov dancing, or in some way using his body. I found his face so expressive, and such a compelling mixture of tough and vulnerable, that I left his dancing and physicality out of my approach. I felt that if I explored just his face I would find something worthwhile.

Michael Imperioli

I made what I felt was a powerful black and white portrait which, given his strong Italian features, wasn’t terribly difficult. Then, because I felt the need to explore further, I used a prop that added its own “attitude” to the picture. The use of reflective materials, mirrors, curved shiny chrome etc. can add features to a portrait that are unusual, surprising and wonderful.

The late Morley Safir, CBS 60 Minutes

For years, I have watched the popular CBS news show,

60 Minutes, on Sunday evenings. When we arrived in NYC many years ago, I wrote Safir asking if he would come down to the studio for a portrait, which he graciously did. Fifteen years later I asked him if he would return. These two pictures express the way photography so movingly charts the passage of time.

Laurence Fishburne

During the shoot he was so “on” and energized that I felt I needed to try to get him psychologically out of the studio and away from the camera in front of him. So I made up a story and asked him to imagine and place himself in the tale. I’d love to hear from readers what you might think the story was that created and led to this gesture. Take a guess, write to me—we’ll share it.

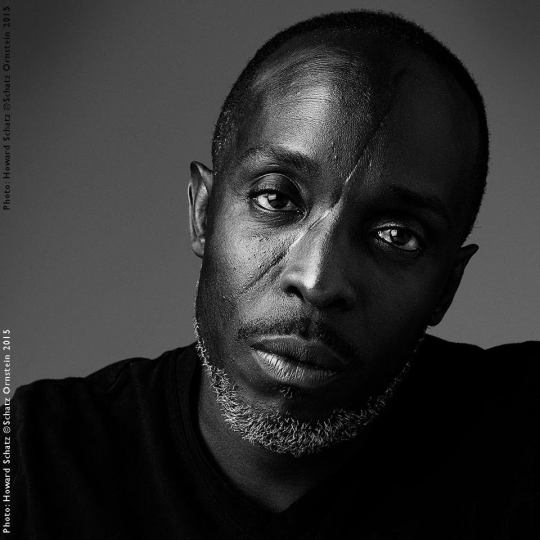

Michael Williams

Williams’s long facial scar (suffered in a brawl outside a bar one terrible night) has made his wonderful acting even more compelling. Despite his tough guy roles, particularly in “Boardwalk Empire,” he has a sweet, almost childlike vulnerability. In the early stages of his career, he was grateful for this opportunity.

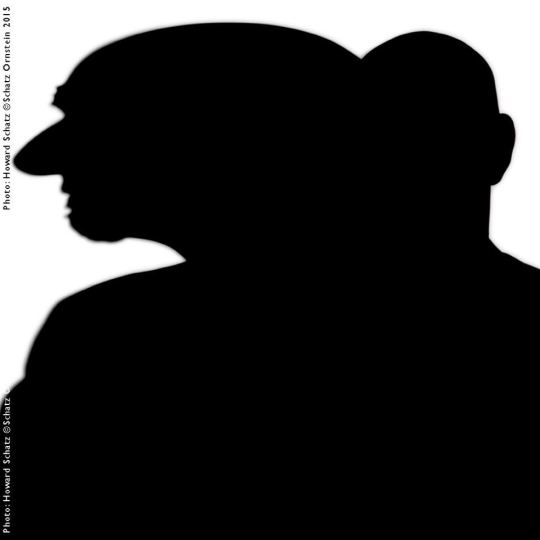

Ben Kingsley

Some sitters have features distinctive enough that they are recognizable without details.

A rule of physics (and thus photography): where there is shadow there must be light (and visa versa). In order to achieve and capture this distinctive shadow there had to be a “hard” contrasty, very small light source—i.e. the left side of his face HAD to be lit. Making it dark was accomplished after I made the photograph; informed by an imaginative treasure hunt for something sui generis.

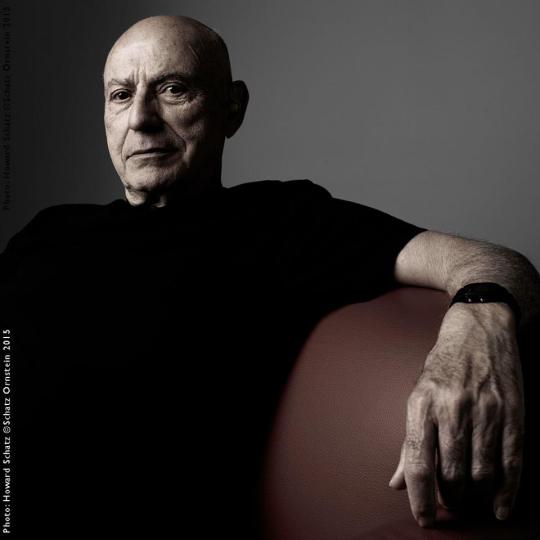

Alan Arkin

I was on the film set of the movie “Grudge Match” starring Sylverster Stallone and Robert DeNiro. Arkin had a part in the film and I made a connection with him when he wasn’t on set, being filmed. I asked if he would “sit” for a portrait for me and that if it turned out well I would send him a print; he said, “Sure.” This portrait had no specific purpose other than the pleasure of making it.

Glitterati Incorporated, the publisher of the Retrospective, Schatz Images: 25 Years is now offering the two- book boxed set at a discount from the original price. The set comes with an 11″x14” print of the buyer’s choice.

http://schatzimages25years-glitterati.com