LYNN’S STORY

Beverly and I recently went to the Public Theater in New York to see the play Mlima’s Tale by Lynn Nottage, and I knew we had to include the playwright in my ongoing project, Above & Beyond.

Nottage is a professor of playwriting at Columbia University in New York

City, a graduate of Brown University and the Yale School of Drama. She

is the only woman to have won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama–twice; the

first in 2009 for Ruined, and the second in 2017 for Sweat. She also won an Obie Award that same year. In 2007, she was awarded a MacArthur “Genius” grant.

Her plays have focused on the plight of women in Africa and early 20th Century New York. The Guardian newspaper wrote that, “Nottage’s two decades of work has garnered praise for bringing challenging and often forgotten, stories onto the stage.”

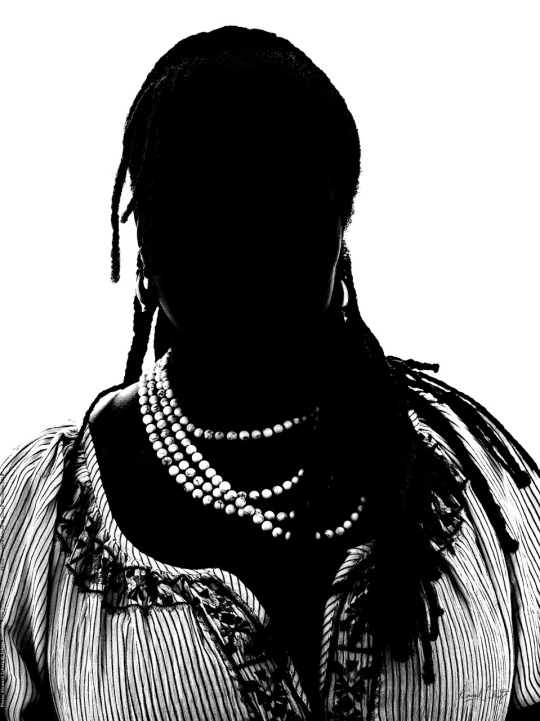

As is my usual approach when making portraits for my series of

remarkable men and women in this current project, I preceded the camera

work with an in-depth interview with the playwright. Not only does this

let me create a bond with my subjects (since photography can be a rather

cool medium), but it gives me a chance to decide what kind of portraits

will best describe the person in front of the lens.

Here’s a shortened version of our fascinating conversation:

HS: I read that you said, “My mother taught me to love

the reflection in the mirror and value my own voice.” I thought that was

so beautiful and I wonder if you could discuss that.

LN: I think that I was blessed to grow up in the

aftermath of the black power movement in Brooklyn, in a very

multicultural neighborhood with parents who were educated and deeply

invested in their blackness. One of the things that I remember about my

mother when I was no more than five years old was that she’d

meticulously color in all of the picture books with brown magic markers

so that when I read books what I saw was people who looked like me.

HS: You’ve written about a 20-year struggle to be

heard, about rejections and disappointments. In contrast, the kind of

success you’ve had in the last ten to fifteen years is remarkable to me.

LN: I’m incredibly tenacious and I think that as an

artist you have to oscillate between grandiosity and despair and those

grandiose moments are the ones in which you really face down all of the

demons and the people who tell you can’t do it.

During my early years, every day was an act of resurrection when I

looked in the mirror and I said you can do this, even though repeatedly I

was told that there wasn’t space for me on the landscape. You know,

when I looked at off-Broadway theaters very few of them were producing

plays by women and even fewer were by women of color. So, the only

person I had to encourage me was myself.

HS: What are the challenges of being a playwright, a woman playwright, a black woman playwright?

LN: I think that’s one of the difficulties now; if

you’re a playwright who’s socially or politically engaged, is that there

is an appetite that has shifted. It is an appetite for things that

entertain, that sort of help you escape circumstances. And I really feel

that my function as a playwright is to reflect back things that are

difficult to see. And, I think that we have become very adept in this

culture of transforming how we see ourselves.

The other part of your question, “is it difficult to be a playwright

who’s a woman of color?” It’s less difficult than it was when I first

began, but it’s still an uphill battle. When I first began, there really

weren’t that many women who were invited onto even the second stages of

off-Broadway theaters. And so one of the things I learned from my

mother is that no one is going to give you an invitation, you just have

to enter the room as if you belong there.

HS: How does one write a play?

LN: I don’t think that there is any one way to write a

play. I believe the content should really dictate what form it takes. I

think that you write a play in the same way you begin any writing

process…you sit down and begin to map out the character’s journey. I

think that when people get into trouble when they’re writing plays it’s

because they don’t know who their character is, they don’t know where

their character is going and they don’t know why their character is

doing what they’re doing.

HS: I read that you make a soundtrack when you begin to write a play?

LN: Yes, always before I begin a play I like to know

the sonic texture. It may take me two to three weeks to figure out what

that is and I select my songs very carefully and I’ll select songs for

my individual characters. It takes me right back to that character’s

feeling and it becomes really a helpful tool.

HS: Does one play sound different from another?

LN: Yes, absolutely. The play Sweat had a very specific soundtrack.

It takes place in 2008 and so I called up music from that period and also music that I felt my characters would be listening to.

HS: What triggers a new play?

LN: That’s really an interesting question and I’m not

entirely sure what triggers a new play because there are moments in

which I feel I have nothing to write about. And then one day, I wake up

and have an idea that I can’t shake, or I’ve read something in the

newspaper, or I’ve encountered someone on the subway and that just

continues to

haunt me.

And if it’s haunted me for about a year I think maybe this is something that I want to spend some time with.

HS: Do you write plays for yourself, or for an audience?

LN: I believe that the audience is my final

collaborator. I think that the medium is designed to be communal and

that’s what I love. I think that when I began writing, I write for

myself and I love that solitary experience. And then what I love about

play-writing is you fold out work slowly and you introduce all of these

wonderful elements beginning with the director and designers and the

actors and then finally you have the audience. And so everyone builds

upon this experience until it becomes something completely different

from what you imagined.

HS: It must be so interesting to see a work that you’ve done become interpreted in a way that you might not have expected.

LN: That’s what’s beautiful about theater–you

surrender part of your creative process to someone else and sometimes

they do things that are absolutely astonishingly beautiful and other

times they do things that make you want to cringe. But that’s part of

this medium. It’s like once a play is published it really in some ways

becomes the possession of many and if you don’t want that then this is

not the medium to work in.

HS: Have you had fights with directors?

LN: Yes, I’ve had disagreements. I’m not someone who

tends to be prone to big fights. I am stern, but I am a negotiator and a

collaborator.

HS: A few others things. How does this current president impact your life now, and the arts?

LN: Well, what I feel about Donald Trump is that he

really is the manifestation of white panic. It feels like the last gasp

of an empire that’s really hell bent on stifling diversity, and I feel

that I am part of the resistance.

And as a writer in this moment, I have to be more assertive. Every day I

think, “What I can do so that Donald Trump does not become normalized?”

Because he’s not reflective of who we are as Americans, and he’s not

reflective of where I want to see this country going.

HS: Isn’t it curious that forty percent of Americans

feel this is normal, and their minds can’t be changed despite the

president’s behavior?

LN: Well, here’s the deal: Forty percent of Americans

don’t believe in evolution. And I think that there lies part of the

problem; we as a species, we as a culture, have always thrived on

evolving. And if you have so many in the country that don’t believe in

evolution, then you know that they’re going to be invested in someone

like Donald Trump who really wants that evolution to stop.

HS: One sees artists who have tremendous creative

moments in their lives, maybe for a decade or two, and then their

creativity fades. Why do you think that is?

LN: I don’t know how to answer that question, though it

certainly seems so. I remember years ago watching an interview with

Whoopi Goldberg and someone asked her a similar question about longevity

in this business and what she thought she’d be doing in ten years. And

she said, “Working.”

LN: And I think that is my mantra–that as long as we

keep working and we keep stretching and we keep being engaged and

curious about the world, then our work will reflect that. And I think

that is what happens with artists who can’t evolve with the

culture–they disappear. So, I think as artists we have to be agile. And

flexible.