For my ongoing “Above and Beyond” portrait series of extraordinary people, I recently turned my lens to a woman who knows cameras well, though she came to photography by an interesting, winding route.

Before she began taking pictures professionally, she studied dance, worked as a union organizer, and spent time in factories, offices and restaurants. Then, in 1974 she picked up her first camera. At the age of 27, she enrolled at CalArts in Valencia, California, to study photography and then received an MFA from the University of California, San Diego.

Since then, Weems has received numerous prestigious awards for her work, including the Prix de Roma, the U.S. Department of State’s Medals of Arts, the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation’s Lifetime Achievement Award, the BET Honors Visual Artists award, and in 2013, a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship Genius Grant.

In 2013 and 2014, Nashville’s Frist Center for the Visual Arts organized “Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video,” a 30-year retrospective of Weems’ work which traveled to New York’s Guggenheim Museum, Stanford University, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Portland Art Museum and other institutions.

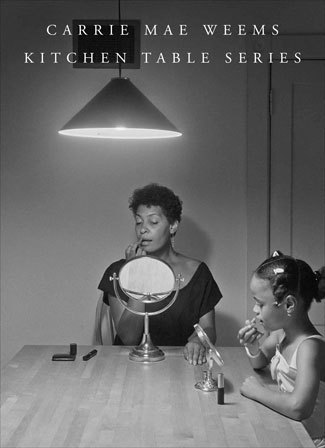

This image was influenced by her “Kitchen table Series” of photographs.

As I always do with participants in my Above and Beyond project, I conducted an interview with Weems. Here are some of the thoughts she expressed.

HS: How does the camera inform how you see the world?

CW: One of the first things I understood immediately about what cameras do is to ease you into the world in a certain way. When I was coming along, the camera was a fascinating tool that really was meant to engage the world. It has been that for me, a wonderful, visceral tool that has allowed me to explore the world and to really think about the world in a certain way. I think of it as a tool of social action.

HS: Though are you not at times surprised taking pictures?

CW: Always. I’m surprised by what photographs reveal to me about who I actually am and about what my interests actually are. For example photographs really taught me that I was interested in architecture. I would come home, process my film, make my prints and look at them and begin to realize, “Oh, Carrie, you’re interested in the ways things are made, and designed and built. You’re really interested in architecture.“

There’s this idea about pre-visualizing what you make, and on the other hand, there’s the surprise of what you’ve made, and ideas around power.

HS: Do you photograph to learn something, or to say something?

CW: Both. I’m deeply curious. I’m really nosy. I’m always out in the world looking at things because I’m trying to understand what they are and then what it means. I photograph a lot out of curiosity. When you have this camera, you follow it. You follow its lead and it takes you into unexpected places and unexpected territory all the time.

HS: Do you feel your work has impact in the world?

CW: I think it’s pretty important that people are telling me they are deeply impacted by this work. That’s pretty phenomenal. I can hope it’s being impactful but I don’t know unless you tell me. Maybe you feel the same way about your own work. At a certain point, the work is simply bigger than you are. My work is bigger than me. “Kitchen Table” is bigger than me. “Kitchen Table” moved through me. I was just like the conduit for something that was higher and larger.

Whether I’m sharing it with African-American women or white American women or Italian women, or Spanish women, or Japanese women, women around the world relate to that piece.

HS: Something visited you at the time?

CW: Yes, it’s just sort of an opening and a channel that only happens rarely in your life. It’s like love. You only get it for a minute with somebody really, really special.

HS: Have you gone through periods when creativity is dulled, or does it remain at a high? Are there peaks and valleys for you?

CW: Of course it changes over time, like all things. Your life is based on a spiral of actions and reactions, and balances and imbalances and then balances again, and then loss and then a rebounding, a regathering, refocusing and re-framing of the possible.

HS: Do you have favorite subjects for portraiture?

CW: I love painting and painters. I was asked to photograph Robert Colescott, a painter, for the Venice Biennale and I made these very particular photographs with him. Working with him opened me up to my relationship to painting, and figuring out another kind of work.

What was my relationship to Black painters? What was my idea about the image of the Black female in relationship to a historical painting and then painters of the 20th century? Though, I realized I loved Monet’s work and the work of Picasso and Duchamp and those brilliant men. But they never ever really made anything that resembled anybody that looked like me. I have this great love affair with these amazing, amazing artists and painters, but they’ve never represented the likes of me.

It was clear I was not Monet’s type, and Picasso, who had a way with women, only used me, and Duchamp never even considered me. But it could have been worse… imagine my fate had de Kooning gotten hold of me.

HS: A few years ago at Stanford, when you were being honored for your work, you said that you were broke and that jolted me. I thought about a successful artist, an artist who’s won a MacArthur Award and has a long list of every kind of award in the world, whose work is known internationally and has been written about positively by every great critic. It was interesting that you would, in front of an audience, reveal that.

CW: I’ve looked at how a woman’s work is valued in the open market, and the difference between the highest paid woman and the lowest paid man of a certain rank. It’s in the millions.

Georgia O’Keeffe said, all the guys like to think of me as the best female painter, but actually I’m the best painter. But the distance between what is paid for her work now, and that of, let’s say, Francis Bacon is 60 or 70 million dollars.

I think that in using this idea of being broke had to do with the ways in which work has been historically valued. I also understand it politically and socially and morally and culturally. What does it mean when we so undervalue the production of women artists?

HS: Does your success get in the way of expressing yourself personally?

CW: I don’t see myself as being successful. I don’t really know exactly what that means. There’s a certain way of course in which I’m comfortable…so why is it that I always assume I don’t really have any money, that I can’t really spend anything, that I always buy things at discount department stores? I think I was brought up that way and so that’s the way I live my life and I don’t really splurge very much. I’ll do a lavish dinner party for a friend, but I would never do it for myself.

HS: You’ve said, “The ever present threat of violence takes its toll.”

CW: This is a huge problem of course. I’ve done many projects around it. I’ve lived around this so I’m highly aware of violence, in particular what it means for African-Americans. But what it means for us as a culture and as a society is also important because it’s crippling; the violence against men and women, against gays, against anyone who is different.

That violence takes a serious toll on the psyche and well-being of people. Those young children in Parkland, those concert goers in Vegas, those children at Sandy Hook… this is not just a problem for African-Americans, this is a problem of our society.

So that when you become afraid to walk down the street, when children are afraid to go to school, this is a nightmare, right? And the stress that it puts on the body, the stress that it puts on the mind, this is awful. And scary. The children are becoming more and more fearful of one another. They’re fearful of going to school, of being in social environments. What happens is that you spend more time doing anything that keeps you out of the larger social sphere, and that’s a problem.

I think that I’m really looking at it more broadly. Yes, I care about what happens to African-Americans, and I’ve done pieces around this like Grace Notes, the performance project that I’ve been working on that’s been touring around the country and opened at the Kennedy Center not long ago. It looks at the policing of the Black male body as a subject of investigation. That’s been very important to me.

HS: I have heard you say that you “had to fight so hard for every single thing.“

CW: I’m a Black woman and so this carries with it a certain kind of weight and a certain kind of meaning. Women typically are disregarded. Women artists are typically disregarded. Historically, they’ve been disregarded so we’ve always had to work harder for our recognition, for a seat at the table. It’s just a part of the social dynamic in which we are engaged and involved in the society in which we live.

It’s predicated on the idea that women are powerless. How you deal with that factor, of course, is the thing that really matters. Being a Black woman, you understand what the limits are. You understand how you’re being looked at, how you’re being gauged or judged or dealt with or not dealt with.

Those are issues that I’ve always had to contend with and I’ve really sort of contended with them usually with the understanding that I’m probably the smartest person in the room. I’m usually the most interesting person in the room, and I’m certainly the hardest working person in the room. I’m usually the most imaginative person in the room.

I realized that for the most part, no matter what, there were no men that were supporting me. They might look at me and smile at me, take me to a nice dinner. They might even think about fucking me, but are they going to give me that job? Are they going to really give me that show? And the answer is no, they will not. They might give me a couple thousand of dollars…but they’re not going to give me the serious dough, the action, the space, the real space to create.

CW: It’s a huge problem for society because for the most part, these extraordinary people who hold up more than half the sky are not being recognized for the extraordinary contribution that they make to the building and the beauty of the world in which we live. And so society then suffers. Children suffer. Women suffer. Men suffer.