Eve Ensler has accomplished many things, including the writing of nine plays. She is best known for her play The Vagina Monologues, written in 1996. The once controversial and hugely influential play has become a classic, translated into 48 languages and performed in more than 140 countries. It won an Obie Award in 1997.

She has received many other awards including a Guggenheim Fellowship and an Isabelle Stevenson Award at the 65th Tony Awards.

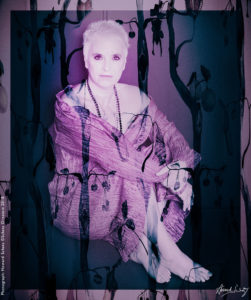

For my project Above and Beyond, I was very pleased to have Eve Ensler come to the studio for a portrait sitting and interview, which follows.

HS: How has The Vagina Monologues, and your work in general, impacted our culture?

EE: When I started The Vagina Monologues over 22 years ago, no one could say the word vagina. We couldn’t say it on television. You could say penis on television, you couldn’t say vagina; people say vagina now, and say it everywhere and on television. It doesn’t seem unnatural, and it doesn’t seem strange.

When I started to do the play the number of women who would come up to me afterwards, would literally line up to talk to me, I thought, great, they’re going to be talking to me about their wonderful orgasms and their sexual desire. In fact, what most women were lining up to tell me was how they’d been raped or battered, or abused. So, that’s why we started V-Day 22 years ago, to see how we could use the play to stop violence against women and girls.

Our movement has allowed discussion about the right to talk about and think about, and protect our bodies. I look at what this next evolution is through the #MeToo movement, or the #Time’sUp movement; all those grow out of the work we’ve done. It’s a continuum.

When I went through airports people would stop me and they would say, I saw you in the Vagina Monologues. Now people stop me and say, I was in the Vagina Monologues. I think this year there were 500 colleges that did the show, and every year there are hundreds. Young women not only have come into their sexuality and feel good about it, but they have become activists, leaders, and people who are fighting for social justice. They’ve become social workers and funders.

HS: Regarding the violence of men toward women. What is that about? Where does it come from?

EE: Patriarchy, which is only 17,000 years old. If you think about humanity, we’re 200,000 years old. Patriarchy occupies a very small period of time within the existence of human consciousness, and I think it is deadly. I’ve thought about this for most of my life, being a survivor of sexual abuse, and incredible violence.

What compels a man to rape a woman who says, “Stop?” What compels men to grab someone’s body at work, or harass someone? Or a father raping his daughter as in my case.

You grow up in a system that has taught you that men have all the rights. It’s first of all about domination, and the belief that there is one gender superior to another with the right to dominate. It’s a belief in the all-powerful father. But really, if you look at what it’s about, it’s about toxic masculinity and bringing up boys to believe, for example, that they can’t be weak; weakness means you’re emotional, that you’re vulnerable, that you’re able to cry, that you’re able to express your longing and desire, and your depth, and your empathy. Empathy is completely ruled out because empathy makes you weak.

If you look at military training, one of the first things they beat out of young recruits are their feelings. You’re not allowed to feel worried, you’re not allowed to feel fear, you’re not allowed to feel vulnerable or terrified, you’re certainly not allowed to feel any empathy for your enemy, who you will be killing, because if you feel for them you will not be able to kill them.

I think we cannot underestimate what happens to young boys when they are told every time they have an emotion, to shut it down. Not to feel. Not to cry. Not to care.

What is in the hearts of men that allows this kind of violence? I think it’s the central question of our times. It’s the same thing that allows us to destroy the earth, it’s the same thing that allows us to separate immigrant mothers and migrant mothers, and undocumented mothers from their children. It’s the hardening of the heart, and that patriarchal kind of bubble is the bubble under which the entire planet right now is suffocating and being incinerated.

HS: Do women have a responsibility in this situation?

The people who are responsible are men, and even the good men, the men who don’t rape, the men who don’t attack, the men who don’t batter, the men who don’t harass women; they are silent bystanders. They are silent participants if they are not standing up in a powerful way to end this violence.

They have daughters, they have mothers, they have aunts, they have wives, they have girlfriends…why isn’t this fight their fight? I honestly think if we’re going to undo patriarchy men have to lead this, because they are the people who benefit from it.

HS: Where was your mother when this was happening to you?

EE: My mother was a poor woman who had nowhere to go, who married a man who had money, then had three children. My mother didn’t have a job, my mother didn’t have work, my mother was my father’s fourth child. She was devoted to my father, she was his child. She served him.

HS: But when you suffered what happened?

EE: I can blame my mother for not standing up, and believe me, I’ve had periods in my life when I did blame my mother, but in the end I have to say, my mother was as much a prisoner to patriarchal oppression as I was. What was she going to do with a violent man who was her husband? She was just as afraid of him as I was. We all were. We lived under his tyranny. There are battered wives, before they reach that point where they are willing to stand up to their abuser, they are the greatest defenders of the abuser. Because to reckon with what has been done to you, to understand the oppression you’re suffering, to step into the pain you are actually feeling is really, really difficult.

I think when you’re abused as a child, in whatever form, sexually or physically, you are a consequence of violence. My whole childhood was about being violated in one way or another, whether I was thrown against walls, or threatened with kitchen knives, or punched in the nose in restaurants. And then the early childhood sexual abuse completely screwed my mind.

I think by the time I was 17 I was an alcoholic. I was already drinking every day, and I was drugging every day. And I grew up in the 60s, and I was stoned all through high school. All of that was just not to feel the horror that was inside of me, and I reached a point where I had drunk and drugged myself to the bottom. I was insanely promiscuous, I didn’t know who I’d end up with every night, I would just go out and…. I grew up believing that if somebody wanted me sexually, I didn’t have a choice to say no, because I had never had a choice to say no. It took me years to understand that if someone wanted me, I could actually say, I don’t want this. Because it had been programmed into me that I didn’t have a choice.

I was very fortunate that when I hit 23 or 24, and I bottomed out, and I was near death, that there were people who intervened, who really took me into a program and helped me recover.

HS: I’ve seen some of your talks with an audience of women. Have you spoken with groups of men?

EE: When I started doing the Vagina Monologues, very few men came to see it. Now when it’s done, it’s half and half in the audience. That’s changed completely. And I can’t tell you how many young men would come up to me and say, thank you for this play, I’ve learned so much about vaginas. My girlfriend was raped, and now I feel like I know how to approach it.

I’ve never hated men. I’ve never felt like men are awful. I think men are irresponsible. I don’t think men are standing up in ways they should be standing up.

HS: When the interview and portraiture had ended and Eve Ensler was at the door, about to leave our studio, I said to her, “There are a number of famous paintings, each of a woman posing on a chaise which have been done by many famous artists” I then described it and showed her images.

“The Dresden Venus” by Giorgione,

“Reclining Venus” by Titian,

“Olympia” by Manet and

“The Grande Odalisque” by Ingres,

“Since you are so in touch with sensuality and your own sexuality would you consider our working together to create such an image of you sometime?” She responded, “I’ll think about it.”

She wrote me a few days later and we set about making plans.

Eve Ensler as “The Grande Odalisque.”